WHY SCRAMBLE? WHY NOT A PEDESTRIAN INTERVAL?

“Pedestrian scramble” is a completely inelegant term for temporarily stopping driver traffic in all directions. Pedestrians are then allowed to cross in four directions in intersectional crosswalks as well as diagonally, for a total of six directions instead of the two directions pedestrians at intersections are so very used to.

The actual name “scramble” sounds like chaos, and it has been called a pedestrian crisscross or diagonal intersection in other places. But that “scramble” name suggests that even when we talk about equity for street users, when it happens for pedestrians they had better move quickly. Despite the name, research at Transport for London has suggested the installation of a diagonal crossing can reduce pedestrian casualties by 38 percent.

The photo above is from Seoul Korea where the scramble intersections have been installed in busy business areas. I am familiar with the scramble intersections in Seoul and they work well. The one requirement though is that there must be large sidewalks and well built walking infrastructure to handle the increased capacity of people that will be using these crosswalks in all six directions.

Some traffic engineers perceive the pedestrian scramble as inefficient as it stops driver traffic in all directions. But that’s a good thing, in that it allows drivers to make left or right turns through the crossing without being blocked by walkers. In Vancouver most pedestrians are hit in intersections during those left and right turn driver vehicle movements.

Vancouver actually was one of the first cities in the world to have pedestrian scamble intersections in the 1950’s. At that time they were called “diagonal” intersections and were placed at Georgia and Granville Streets, Hastings and Granville and Pender and Beatty Streets in 1953. There was also a pedestrian scramble installed in 1965 at the “T” intersection of Columbia and Church Streets in New Westminster.

There is a great story in the Vancouver Sun from December 2nd 1953 when Vancouver Traffic Superintendent Gordon Ambrose decided to treat pedestrians like car drivers at these intersections. In one day with twenty “point men” in a “flying squad” 107 tickets were issued to walkers. These were all court summons for walking not according to the “walk” signal, or on a “wait signal” or getting caught crossing the diagonal intersections when the signal for walking changed.

The use of a pedestrian scramble in high pedestrian traffic areas was mentioned in the 2012 2040 Transportation Report prepared by the City of Vancouver, but turfed because of concerns of crossing for sight impaired individuals.

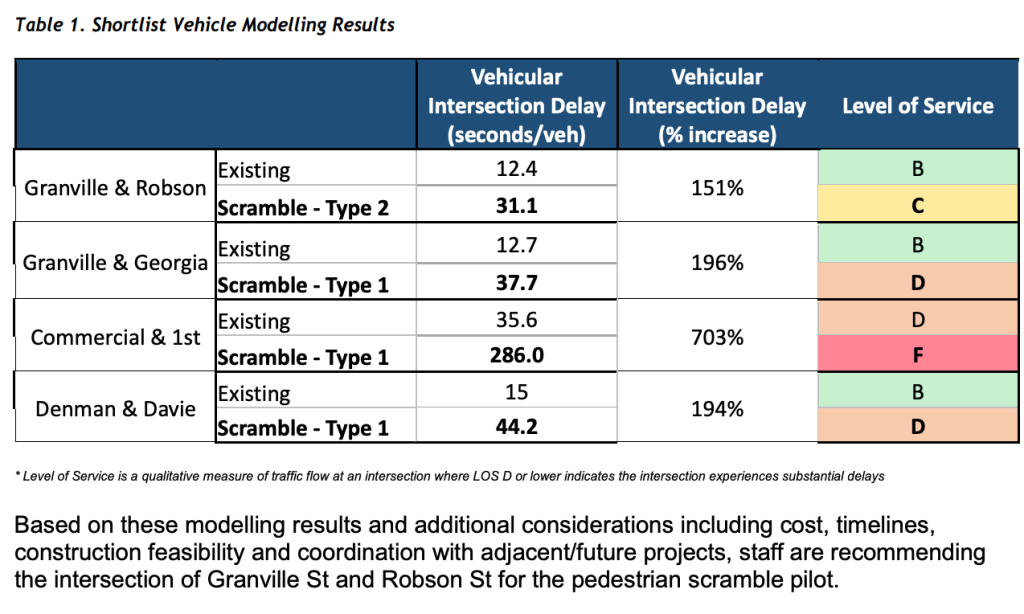

The very capable Paul Storer who is Vancouver’s Director of Transportation has written a Council report based upon a request from an ABC Councillor to create a pedestrian scramble. Mr. Storer reviewed four high pedestrian traffic intersections in the downtown area and narrowed down the candidates to the Granville and Robson Street intersections. There are some concerns with transit delays, and you can read the analysis in the report.

Surprisingly this Council actually allocated half a million dollars from the Growing Community Fund for this project, but Mr. Storer’s project will only require 100,000 to 200,000 dollars for this initiative. Perhaps instead of a splashy downtown six way criss cross, this Council could consider installing more Leading Pedestrian Intervals at more intersections. They are not as flashy, but by allowing pedestrians a three to seven second second head start in an intersection before drivers get the green light reduce driver crashes into pedestrians by 60 percent. The cost is less than a few thousand dollars per intersection for something that saves lives and prevents serious injury for vulnerable road users.

You can read more about Leading Pedestrian Intervals (LPIs) here.

Here is a video from the City of Surrey which has installed many Leading Pedestrian Intervals as part of their Vision Zero Work with Shabnem Afzal. Ms. Afzal is now the Director of Road Safety Policy and Programs at ICBC, the Insurance Corporation of British Columbia.

images Yonhapnews, Vancouver Archives City of Vancouver